Theoretical Roots of ThingLink: From Vygotsky to Virtual Learning

The foundations of ThingLink are rooted in the socio-cultural theory of learning developed by Lev Vygotsky. My own journey began in 2003 at the Center for Activity Theory and Developmental Work Research at the University of Helsinki, Finland, where I started as a doctoral student. At the center, reading Mind in Society and engaging in discussions about social interaction, cultural mediation, and the role of tools and technology in learning was a rite of passage.

It was during the first years of my studies that the core idea behind ThingLink began to take shape: If all learning is inherently interactive, shouldn’t our digital tools be designed to support interaction and guided exploration within meaningful, real-life contexts?

This post outlines three key principles from Vygotsky’s work that continue to guide our thinking. They are not just academic references – they’re the reason ThingLink exists.

1. Learning Is Inherently Interactive

From the perspective of Vygotsky’s cultural-historical theory of learning, interaction is not simply a method of acquiring knowledge – it is the foundational mechanism through which learning occurs. All higher cognitive functions, he argued, first appear on the social plane between individuals, and only later on the individual plane, internalized by the learner (Vygotsky, 1978). This process is most famously articulated in the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) – the distance between what a learner can do independently and what they can do with guidance from a more knowledgeable other.

This foundational belief – that cognition is socially co-constructed – guides ThingLink’s pedagogical approach. Just as a child acquires language through culturally mediated interaction in the physical world, ThingLink assumes that the basic logic of learning does not change in virtual environments. Learning remains fundamentally interactive and dialogical, even when mediated by technology.

By layering information, questions, voice, and multimedia elements directly onto visual environments, ThingLink provides a socially and semiotically rich context for knowledge construction. These interactive touchpoints operate as digital tools of mediation, echoing Vygotsky’s assertion that psychological tools (like language and symbols) are central to cognitive development. In doing so, ThingLink turns passive materials into interactive spaces where learners participate in meaning-making rather than merely consume information.

“Learning awakens a variety of internal developmental processes that are able to operate only when the child is interacting with people in his environment and in cooperation with his peers.”

Vygotsky, 1978, p.90

ThingLink’s pedagogical foundation builds on this idea: the logic of learning as an interactive, socially situated process does not fundamentally change in virtual environments. On the contrary, the importance of interaction becomes even more pronounced when learners are navigating digital or immersive spaces, where meaning-making must be actively constructed through guided attention, contextual cues, and shared experiences.

By transforming any image, video, or digital environment into an interactive space layered with multimodal touchpoints, ThingLink mirrors the culturally mediated learning process described by Vygotsky. These interactive layers – hotspots that integrate text, voice, video, questions, and links – function as digital mediational tools that support attention, provide scaffolding, and encourage learner agency. They turn static materials into participatory learning environments, reinforcing the understanding that knowledge is not transmitted but co-constructed.

In this way, ThingLink does not simply present information; it orchestrates a learning dialogue between the learner and the environment – mirroring the real-world interactivity essential to all learning.

2. Technology as a Mediating Tool

Vygotsky emphasized that human learning and cognition are always mediated by tools and cultural artifacts – these include both psychological tools (e.g., language, symbols, signs) and technical tools (e.g., maps, devices, and now, digital platforms). These tools do not merely support action; they reshape the very structure of mental functions (Vygotsky, 1930/1978, how we perceive, interpret, and engage with the world. As he famously put it, “The tool changes the process” (Vygotsky, 1930, cited in Wertsch, 1985). Immersive technologies shape not only what we learn, but how we learn.

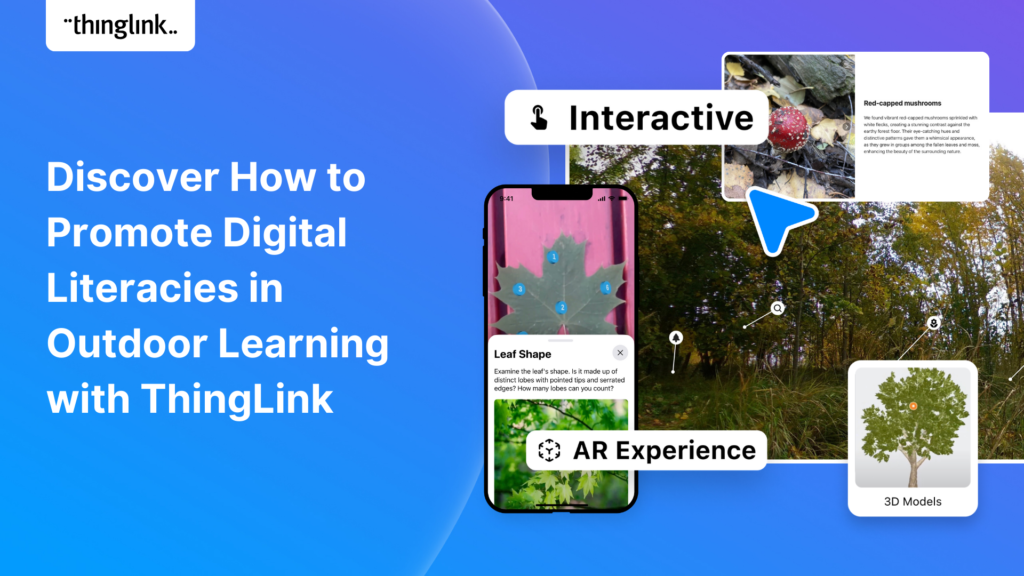

ThingLink embodies this mediational function by allowing educators to design and scaffold learning environments using interactive hotspots. Through the use of interactive hotspots, the platform enables educators to embed guidance, context, and action directly within multimedia environments. These hotspots serve as navigational and cognitive markers, guiding learners’ attention, providing embedded support, offering clarification or multimodal explanations, and organizing the progression through complex or unfamiliar material, structuring the learning journey. Much like scaffolding in a physical classroom, hotspots create a semiotic architecture, each hotspot becoming a bridge from one context to another, enabling non-linear, curiosity-driven journeys through authentic spaces. In this way, the platform supports both guided instruction and learner agency, aligning with the Vygotskian notion that effective learning environments balance structure and freedom within a culturally mediated framework.

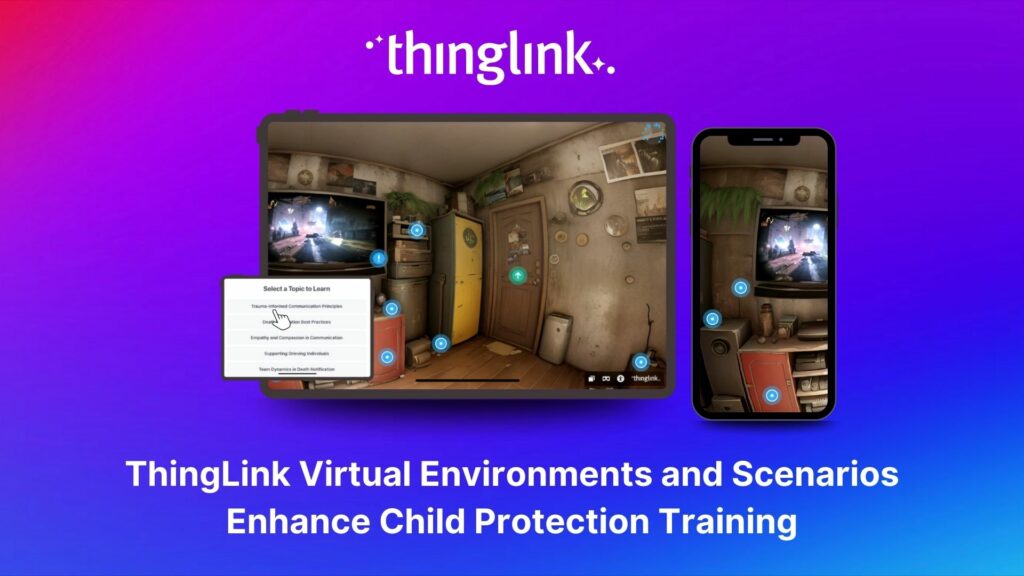

The mediational power of technology in ThingLink goes beyond structuring content. It also lies in its ability to transcend the physical limitations of traditional learning environments. In Vygotsky’s view, tools do not merely support action – they can expand the field of perception and transform experience. This is precisely what ThingLink enables in immersive learning: learners can visit a hospital, a cultural monument, or a manufacturing plant remotely, engaging with content in authentic, situated contexts. The ability to move from one environment to another through action points fosters structured exploratory learning, grounded in real-world relevance. Where Vygotsky noted that tools extend human capability beyond immediate physical and biological limitations, immersive content technologies such as ThingLink can remove the spatial and contextual constraints of traditional schooling.

“Every function in the child’s cultural development appears twice: first, on the social level, and later, on the individual level; first, between people (interpsychological), and then inside the child (intrapsychological).”

Vygotsky, 1978, p.57

3. Apprenticeship in the Digital Age: The Role of the More Knowledgeable Other

In Vygotsky’s cultural-historical theory of learning, the “more knowledgeable other” (MKO) is a cornerstone of development. It refers to someone – typically a teacher, parent, or peer – who possesses more advanced knowledge or skill and can support the learner’s progression within their Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). Learning, in this model, is a social apprenticeship: the novice is guided, scaffolded, and gradually supported toward independent competence.

As we enter the age of AI, the notion of the MKO is expanding. While human mentors remain irreplaceable in shaping complex reasoning, empathy, and values, new digital tools – including AI and immersive technologies – can serve as distributed forms of mentorship, providing responsive, asynchronous guidance in learning environments that are no longer bounded by time or place.

ThingLink enables educators to create structured, guided learning experiences that mirror this apprenticeship model in a digital context. Through the use of audio narration, step-by-step instructions, embedded prompts, and curated visual environments, teachers can embed their presence into the learning space—even when they are not physically co-present. This aligns with Vygotsky’s idea that mediation by tools can extend the role of the educator, allowing teaching to take place across spatial and temporal boundaries.

These immersive lessons offer learners a sense of mentorship and continuity: they can hear the teacher’s voice, follow instructions, and engage in inquiry-based learning within an environment designed to model expert understanding. In doing so, ThingLink operationalizes a new form of asynchronous apprenticeship, in which learners can access expert guidance at their own pace, within authentic and contextual learning scenarios.

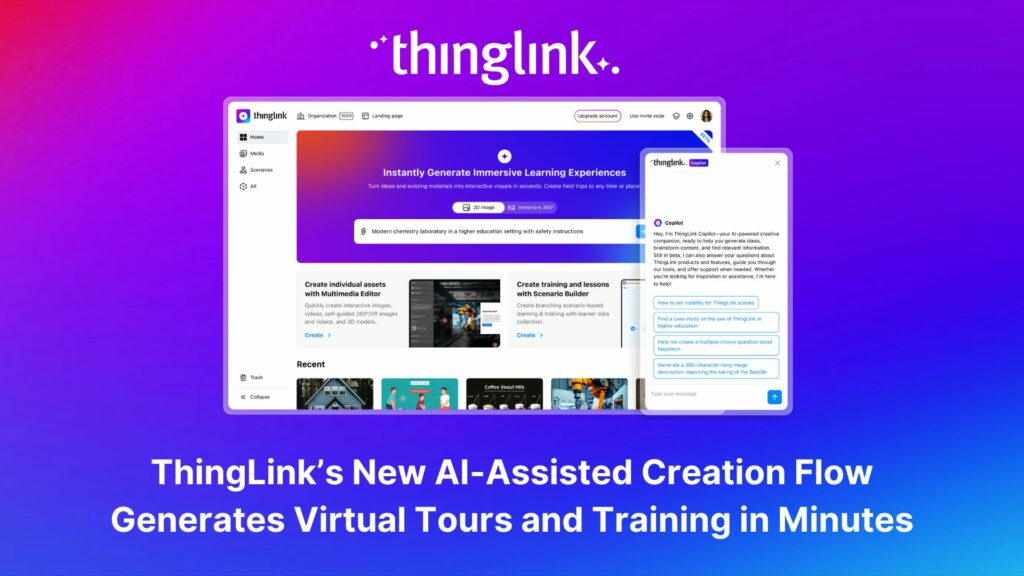

Looking forward, our team at ThingLink will be exploring how AI-assisted tutors and conversational agents can become integrated into these experiences – offering personalized feedback, answering questions, and adapting guidance based on learner needs. While AI may serve as an initial MKO for knowledge acquisition, its optimal use lies in supporting educators by handling routine explanations or low-level queries. This shift allows human teachers to reclaim time for what Vygotsky called higher psychological functions: reflection, reasoning, dialogue, and problem-solving – all of which thrive in human-to-human interaction.

In this vision, educators and AI do not compete; they collaborate in scaffolding learner growth. Teachers remain central, shaping the learning environment, setting ethical frames, and cultivating the kinds of thinking that define deep understanding – while AI and immersive platforms like ThingLink provide the structure and flexibility to make that vision scalable and inclusive.

“Instruction is only useful when it moves ahead of development. Then it awakens and rouses to life those functions which are in the process of maturing.”

Vygotsky, 1978, p.89

Conclusion: Theory into Practice, and Questions for the Future

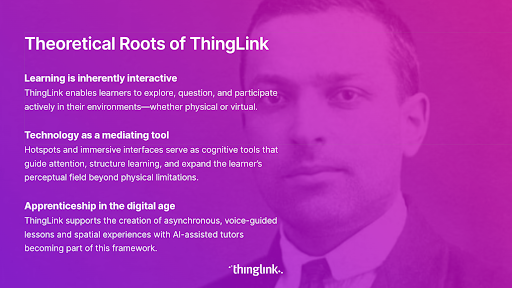

The theoretical foundations of ThingLink draw from Vygotsky’s socio-cultural theory of learning, particularly three core principles that continue to shape our platform and vision:

- Learning is inherently interactive.

Learning occurs through engagement, dialogue, and shared meaning-making. Digital tools, like ThingLink, must reflect this by enabling learners to explore, question, and participate actively in their environments – whether physical or virtual. - Technology as a mediating tool.

Vygotsky argued that tools don’t just support thought – they shape it. Hotspots and immersive interfaces serve as cognitive tools that guide attention, structure learning, and expand the learner’s perceptual field beyond physical limitations. By recreating authentic contexts digitally, we make learning more equitable, accessible, and anchored in real-world relevance. - Apprenticeship in the digital age.

The presence of a “more knowledgeable other” remains vital, but in today’s landscape, that guidance can come from a teacher, a peer, a digital mentor – or even AI. ThingLink supports the creation of asynchronous, voice-guided lessons and spatial experiences, and we are now exploring how AI-assisted tutors could become part of this framework, freeing up educators to focus on higher-order thinking and personal connection.

These principles are not static. As immersive technologies evolve and AI becomes more integrated into education, new questions emerge that merit further research:

- How can AI function effectively and ethically as a “more knowledgeable other” in the learning process?

- What design frameworks best support equitable access to immersive, context-rich learning experiences?

- How do digital mediation tools like hotspots impact attention, retention, and conceptual understanding in complex subjects?

- What are the long-term cognitive and social effects of learning in digitally reconstructed environments?

At ThingLink, our goal is to keep these questions open – and to invite collaboration across research, design, and practice. As we continue building tools for spatial and immersive learning, we remain grounded in the theory that inspired our journey: learning is always social, always mediated, and always evolving.